Sister Monica Kostielney arrived at Michigan Catholic Conference in 1972 as a volunteer working to oppose an abortion ballot proposal. She was a Religious Sister of Mercy who had already embarked on a teaching career.

But once she came to MCC, she never really left.

“I remember a priest involved in the opposition movement saying that if he saved even one life, he knew it would be worth it,” she told the Diocese of Lansing’s Faith magazine in a 2006 interview.

“When he said that, I experienced a moment of clarity as if Jesus had walked up and called me by name. I had never felt that before and never have since.

“I knew I was called to get involved, too.”

Consider it Sister Monica’s very own “call within a call.” That was how St. Mother Teresa of Calcutta described her decision to leave her position teaching in India to go to the streets and serve the poorest of the poor.

Responding to the call within a call was what cemented Mother Teresa’s legacy of service. The same can be said for Sister Monica and her legacy after she responded to her own call within a call.

What started as a stint volunteering to defeat an abortion proposal began a nearly forty-year career at MCC that took Sister Monica to the role of president and CEO of the statewide organization, the first and only female to do so at this point.

“Sister Monica Kostielney has dedicated her vocation to the dignity of human life, educational justice, and concern for the poor among us.”

Most Rev. Allen Vigneron, Detroit Archbishop Emeritus and former Chairman of the MCC Board of Directors

Starting from when she began at MCC and throughout her tenure as the fifth executive of MCC, Sister Monica was an instrumental figure in promoting the common good on a statewide level. Sister Monica’s career at MCC, especially as its leader, left a lasting impression on the organization.

“Her legacy is a legacy of leadership,” said Joe Garcia, who worked alongside Sister Monica as a public policy advocate for MCC during the 1970s. “She forged a path for the conference and for the Church … in articulating the Church’s position to elected leaders in a way that was neither offensive, but more of a guidepost for ‘Here’s what we believe and here’s what we think is the right thing to do.’”

Simply put, Sister Monica was “among the most consequential women in the Capitol community and the Church during her thirty-eight years with MCC,” said Paul Long, who succeeded Sister Monica as president and CEO of MCC in 2010 after working with her the previous 22 years.

Along the way, Sister Monica embodied and advanced MCC’s mission to bring the Gospel to the public policy sphere for the purpose of improving the state of Michigan as a whole.

“Our compelling interest is in what we believe is the common good, not that we’re trying to promote Church teaching,” she once told Faith magazine. “Rather, that social justice is a constitutive element of the Gospel, and those who are most vulnerable need to be protected.”

‘Completely Dedicated’ to the Church and Its Teachings

Sister Monica’s advocacy career with MCC, and indeed her leadership of the organization, was reflective of the broad spectrum of Catholic social teaching and its application to public policy.

“Whether the issues be discrimination, abortion, assisted suicide, capital punishment, access to quality education or justice for immigrants, under the leadership of Sister Monica Kostielney and her dedicated staff, the Conference has become a strong voice of advocacy in our state capitol,” said Cardinal Adam Maida, Archbishop Emeritus Vigneron’s predecessor as both Detroit archbishop and Chairman of the MCC Board of Directors.

One of her most notable achievements was helping MCC defeat a proposal that sought to legalize assisted suicide in Michigan. Sister Monica oversaw an award-winning statewide education campaign to engage and mobilize Catholics against the issue, as well as a coalition of organizations to campaign against the ballot initiative, which was soundly defeated in 1998.

As president and CEO, she oversaw MCC’s work to help pass a ban on the partial-birth abortion procedure, as well as the first and most comprehensive state ban on human cloning in the country in 1998. She also worked with a statewide coalition to thwart multiple attempts to establish capital punishment in this state. Toward the end of her career, Sister Monica also led MCC against a proposal to allow for embryonic stem cell testing, and another that provided greater opportunities for women and minorities in society.

As a religious sister who spent her early years teaching, Sister Monica was dedicated to promoting justice in education—particularly in empowering parental choice and ensuring nonpublic schools had access to adequate resources.

Sister Monica led MCC’s support of two ballot initiatives to bolster parental choice in their children’s education through state-issued funding vouchers, which aligns with the Catholic perspective that parents have the right to direct their children’s education.

Earlier in her advocacy career, she was present as Gov. Jim Blanchard signed into law MCC-backed legislation requiring school districts to provide transportation to nonpublic school students to off-site auxiliary services classes.

Sister Monica understood the Church’s principle of putting the needs of the poor first. She was appointed co-vice chair of Governor Jim Blanchard’s committee on welfare reform and later ran a two-year education campaign for Catholics in the pews titled, “A Call to Solidarity with the Vulnerable Citizens of Michigan.”

It was under Sister Monica’s leadership that MCC helped to enshrine the definition of marriage as between one man and one woman in the state constitution by a vote of the people in 2004.

No matter the issue, Sister Monica was, as Diocese of Lansing Bishop Earl Boyea said upon her retirement in 2010, “completely dedicated to the Catholic Church and especially to Her social teachings.”

Sister Monica understood that to advocate for Church teachings did not always mean achieving policy success. Instead, it was about being faithful to the Gospel.

“Our advocacy voice is sometimes welcomed and other times rejected,” Sister Monica said. “Nevertheless, we maintain an unwavering commitment to the principles of Catholic social teaching as we seek to shape a more just world.”

From Teacher to Trailblazer

Sister Monica was born and raised in Michigan. The eldest of two children—her sister Mary served as chair of the Jackson, Michigan city council in the 1990s—Sister Monica was born November 15, 1937, in Detroit, where she attended St. Francis of Assisi Parish Elementary School and Our Lady of Mercy High School.

In 1955, she entered the Religious Sisters of Mercy, Detroit Province, and took her final vows in August 1958. She received her Bachelor of Arts degree from Mercy College of Detroit in 1960 and her Master of Art’s degree in English and Medieval Studies from the University of Detroit in 1966.

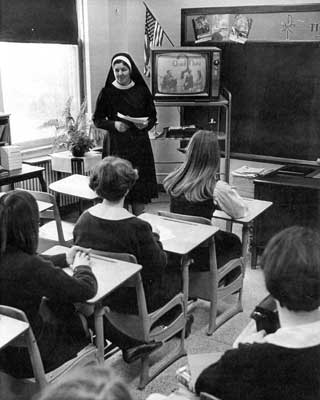

Prior to joining MCC, Sister Monica taught at several schools in the Grand Rapids area, including St. Francis Xavier, Muskegon Catholic Central, St. Simon, St. Elizabeth, and Mt. Mercy Academy.

While a teacher she also completed several graduate courses in administration at Columbia University’s Teaching College in 1968.

During her teaching career, when her order suggested she try something new, Sister Monica figured that it might be another master’s degree. The volunteering stint with MCC changed everything, and it led to Sister Monica becoming a trailblazer.

As the first female leader of MCC, she also became the first female president of the National Association of State Catholic Conference Directors (NASCCD). She was also the first woman to be honored with the St. Thomas More Award from the Catholic Lawyers Guild of the Diocese of Lansing.

“I was always just so impressed by the barriers that she broke with this very, I would say, quiet grace,” said Jenny Kraska, executive director of the Maryland Catholic Conference, who met Sister Monica as part of their participation with the NASCCD. “She really exemplified that leadership wasn’t about power, but about service and integrity. She led with a heart that was truly devoted to the people that she served and the work that she was doing.”

Kraska noted that Sister Monica rose to prominence in the Church at a time when there were not many women in leadership, “so it was extraordinarily significant that she did.”

Sister Monica was a strong advocate for women, including having served as a member on a Michigan Supreme Court panel on gender bias. She was once asked in an interview about how she dealt with women’s issues as a woman in power, and Sister Monica recalled a conversation she had with Edmund Cardinal Szoka, former archbishop of Detroit and chairman of the MCC Board of Directors.

“Cardinal Szoka said to me, ‘You know, I never hear you talk about the women’s issue.’ And I said, ‘Cardinal, why be equal when you’ve always been better?’ Nobody’s ever mentioned it since,” she said.

A Reputation for Integrity

As a result of her extensive public policy experience around the Capitol, Sister Monica was sought after by state officials for her expertise and leadership, having served on several state-appointed committees throughout her career.

Former Gov. John Engler and Lt. Governor Connie Binsfeld in 1998 described Sister Monica as being “steadfast as an advocate for children and families, and vulnerable members of society.”

Sister Monica’s personal qualities—honesty, integrity, and intelligence, to name a few—ultimately helped her be successful in the realm of public policy advocacy, said Garcia, the policy advocate and Sister Monica’s former coworker.

Paul Long, the current MCC CEO who was hired by Sister Monica and represented MCC in public policy advocacy at the Capitol under her direction, said she “was known by everyone in the Capitol community” and that she evidenced “a deep love for every human person” who came across her path.

In a speech Long gave honoring Sister Monica at her retirement, he described her as someone who could converse “with popes and princes of the Church as easily as with the person who cleaned the YMCA, or the gentleman who manned the toll booth at a downtown Lansing parking lot, as well as with governors, university presidents and people who work in the automobile plants.”

Sister Monica was described by Kraska as having a “gentle humor about her” that was useful for providing levity and calm to whatever situation she was in, either within policy advocacy or navigating internal Church politics.

Kraska recalled an instance when she was out to dinner with Sister Monica and another colleague, and when they were offered a dessert menu, Kraska and her other colleague declined. Sister Monica, however, said, “of course we’re going to see the dessert menu.”

“She looks at us, and she’s like, ‘Look, we do really hard work … oftentimes, it is a thankless job. One thing we always need to remember is to always have dessert,’” Kraska recalls Sister Monica saying that night. “It is just something that has always stuck with me. It’s something that I think of every time we go out with colleagues, in honor of Sister Monica, we always get dessert.”

Another crucial factor to effectiveness in public policy advocacy is a commitment to relationship-building, something Sister Monica understood well.

“My years and experiences have helped me understand we are all alike. Underneath we all have the same hopes and desires,” she told Faith magazine in 2010. “Everyone has a basic goodness and wants the freedom to be his or her true self and choose the good. If we love others and they truly know they are loved, that forms the best foundation for any relationship.”

Perhaps what helped Sister Monica excel at relationship-building was her ability to see God in others, something all Christians are called to do.

“When you meet people of differing persuasions you realize the truth that we are all made in the image and likeness of God. Republican or Democrat, governor or custodian—it makes no difference,” she said. “We get to know God through people, and people get to know God through us.”