Catholic Schools Set the Academic Bar High

Catholic schools have long had a reputation for academic excellence. The bar is set as high as families and students want to go.

Brynn Anderson, a senior this past year at Lansing Catholic High School, said she’s had the opportunity to pursue her “passion for learning languages” by taking courses in Latin, French, Japanese, and ancient Greek. Anderson credited it to “the choices my family made in finding an environment that nurtured my academic curiosity.”

Many Catholic schools intentionally keep class sizes small to provide the individualized learning experience that most parents want for their children.

“We don’t want to let anyone slip through the cracks, whether that’s someone that’s already advanced at their level, and we do different things to keep pushing them, or someone who is behind, and we have support to push them,” said Brenda Mescher, principal of St. Charles Borromeo Catholic School in Coldwater.

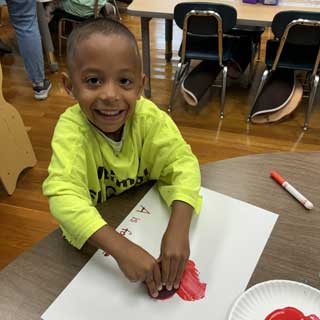

One family benefiting from the individualized approach at St. Charles Borromeo is Denise Parsell and her eight-year-old son Ben, who is entering third grade. Parsell encouraged Ben’s teacher to challenge her son academically this past year, and that is what she did.

“[Ben’s teacher] has a totally different set of spelling words for different levels of kids. She makes sure the reading is at different levels for the students,” said Parsell, who is a high school teacher at a nearby public school and has experienced the fruits of Catholic education in her career.

“I think the [St. Charles] kids are much more advanced … when they come into the high school, [they] are often far ahead of the public education students,” Parsell said, who attributed it to “a really strong work ethic.”

The work ethic extends beyond the classroom, as most Catholic schools incorporate extensive community service into their student formation. Students of Nouvel Catholic Central in Saginaw collectively contribute 10,000 service hours annually to the local community, said Dan Decuf, head of school for Nouvel Catholic Central.

In Warren, while De La Salle Collegiate High School often gets attention for its athletics, it was also featured when the entire student body participated in the school’s annual day of service.